Writing recently in Socialist Worker Martin Smith offered this as a thing to do after the March 26th demonstration: “If we really are going to stop all the cuts then co‑ordinated strikes and a general strike is where this movement has to go.”

In much the same way that your tool box under the stairs has a varied, specialised and seldom used bunch of equipment so too does the knapsack of revolutionary Marxism. And, as with home maintenance, it’s important to know what to use when. Pliers are not great for drilling holes. General strikes are a bit like that. You’d normally expect to have them when the working class is well organised and self confident. As anyone with a passing acquaintance with trade unions at the moment can tell you that rules out big chunks of the working population in Britain.

We will return to the suggestion Martin mentions of an occupation of Trafalgar Square shortly but it doesn’t seem like a great idea. Most people will be slinking off to cafes, pubs and the homeward coach.

Here is what Chris Harman had to say on the matter of general strikes. It includes “… the general strike was a panacea proposed by people who were not prepared to confront the immediate tasks facing the working class.” However don’t trust one sentence possibly ripped out of context. Read the whole article.

THE IDEA of the general strike is nearly as old as the working class movement.

It was first elaborated in the 1830s, in Britain, by William Benbow, who was associated with the ‘physical force’ wing of Chartism. He propagated the call for a ‘national holiday’ – a cessation of work by the whole working class which, he held, would achieve a quick victory for the workers’ movement. And the first experience of anything like a real general strike came soon afterwards, with the ‘Plug Riots’ which swept Lancashire and Yorkshire in 1842.

There was no other experience of a general strike for half a century, until the Belgian general strike for the suffrage in 1894.

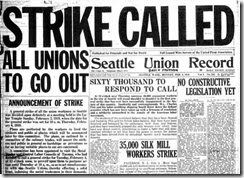

But the question of the general strike has come to the fore in virtually every major upsurge of the class struggle in the twentieth century. So there were general strikes in St Petersburg in October 1905, in Belfast in 1907, and in Spain in 1917. The ‘year of revolution’, 1919, saw a rash of general strikes – in Central Germany, Berlin, and Bavaria, in Seattle, Vancouver and Winnipeg, in Barcelona, in Belfast.

Further general strikes followed in Germany in 1920, Berlin in August 1923, Hong Kong and Shanghai in the mid 1920s, Britain in 1926, France in 1936, German occupied northern Italy in 1944, in East Germany in 1953, Hungary in 1956, Belgium in 1961, France in 1968.

The first Marxist discussion

The contrast between the nineteenth century and the twentieth century is not accidental. The general strike is a form typical of class struggle in large scale modern industry.It comes to the fore when the development of the class struggle has reached the point where action in one industry has an immediate impact upon every other industry and upon the state. The class struggle in such a situation can no longer be confined to individual combats with this or that employer, but has to confront the generalised power of the employing class. And that means the general strike comes to the fore with the transition from the period of ‘free competition’ capitalism to that of monopoly capitalism and state capitalism.

That is why the first serious Marxist discussion of the mass strike is Rosa Luxemburg’s brilliant pamphlet, The Mass Stride, the Political Party and the Trade Unions, written in 1906.

Until then Marxists had tended to see mass strike activity as little more than a form of training which would teach workers the merits of political action.

So Engels, for instance, was absolutely scathing in his criticism of the Bakuninists for raising the slogan of the general strike in Spain in the early 1870s. He said they were calling upon the workers to sit with folded arms, while the key question was one of direct, insurrectionary activity to establish a radical republic.

In the early 1890s Engels returned to the theme. He criticised Jules Guesde, the French Marxist, for adopting the general strike slogan, and he repeated his arguments a couple of years later in a letter to Kautsky, the leader of the German socialist movement. He insisted that the general strike was a panacea proposed by people who were not prepared to confront the immediate tasks facing the working class. Instead of talking, about concrete action that was necessary, they simply spread the illusion that all you had to do was wait until the whole working class was persuaded to stop work simultaneously. Then the class enemy would collapse without struggle.

Engels’ arguments were not drawn out of thin air. They were a distillation of the historical experience so far, from someone who had witnessed at first hand the struggle of the British working class in the 1840s and the revolutionary upheaval of 1848. This experience taught him that the most vital thing at every great upsurge of the workers’ movement was to know how to move from humdrum, day to day economic agitation to confronting the question of state power.

In this, his arguments were not all that different to Lenin’s in 1902 and 1903 when he insisted the central divide within the workers’ movement was between those who saw the all-Russian insurrection as the goal, and those who avoided this central political issue.

But in some of Engels’ later writings a trend can be found which became all dominating in the Marxist movement of the 1890s and early 1900s in Western Europe and North America. This was to see political action as meaning electoral activity. The ‘orthodox’ Marxist parties – the SPD in Germany, the Guesdists in France, the SDF in Britain, the PSI in Italy, the PSOE in Spain – all saw politics as comprising of a mixture of Marxist propaganda and electioneering, virtually ignoring struggles in the workplaces.

The Russian revolution of 1905 showed in practice how the struggles of large scale industry flow over to become directly political struggles. Economic struggles by individual sections of workers gave new confidence to other sections of workers, until people felt confident enough to raise political demands. And mass, general strike action over these political demands in turn gave still more sections of workers the confidence to fight over economic demands. The economic became political and the political economic. And at the head of the economic-political struggle arose a new form of organisation, the soviet or workers’ council, which showed how the question of power could be posed in a new way (although no one saw its full significance for another 12 years).

Rosa Luxemburg’s pamphlet was the first attempt to generalise these lessons from eastern Europe to western Europe. The discussion it provoked within the German workers’ movement prefigured the great split which was to take place throughout the world workers’ movement in the the course of World War One – between those who stood for using the existing institutions of capitalist society to carry through reform and those who stood for fusing industrial and revolutionary political struggle to overthrow existing institutions. (Rosa herself, however, did not see the need in 1906 to draw organisational conclusions from the division over this question, as compared with Lenin who did see the need for such a division in Russia, but not elsewhere, over the question of preparing for the insurrection.)

A specific demand

This split found organisational expression on a world scale with the formation of the Communist International, as an ‘International of revolutionary action’ in 1919. The theses, resolutions and manifestos of its first five congresses, from 1919 to 1922, are marked throughout by an understanding how economic and political forms of struggle fuse in a revolutionary upsurge of the class.However, both Rosa Luxemburg and the leaders of the Communist International in its earlier years followed in Engels’ footsteps in one important respect. They did not raise the slogan of the general strike at all times and under all circumstances. Rather they regarded it as a specific demand to be raised at particular, concrete points in the struggle.

So, for instance, Rosa Luxemburg could write in a letter from Warsaw in January 1906:

‘Everywhere there is a mood of uncertainty and waiting. The cause of all this is the simple fact that the general strike, used alone, has played out its role. Now, only a direct, all-encompassing movement in the streets can bring about a solution ...’

Ten days later another letter spelt out what she meant: ‘The coming phase of the struggle will be that of armed rencontres‘ – the sort of insurrection that was already being attempted by the Bolsheviks in Moscow.

The same understanding of the role of the mass strike and refusal to fetishise the particular slogan of the general strike characterised the early Communist International. So there is hardly a mention of the slogan of the ‘general strike’ in its documents.

Drawing on the experience of these early years, Trotsky, writing in September 1934, insisted, ‘the world experience of the struggle during the last 40 years has been fundamentally in confirmation of what Engels had to say about the general strike’. Trotsky then went on to say that the effectiveness of a general strike depended on concrete circumstances. If the government was weak, it might ‘take fright at the outset’ of the strike and ‘make only such concessions as will not touch the basis of its rule’.

But:

‘If the army is sufficiently reliable and the government feels sure of itself, if a political strike is promulgated from above, and if at the same time it is calculated not for decisive battles, but to "frighten the enemy", then it can easily turn into a mere adventure and reveal its utter impotence’.

Trotsky describes how such bureaucratic mass strikes are organised:

‘The parliamentarians and the trade unionists perceive at a given moment the need to provide an outlet for the accumulated ire of the masses, or they are simply compelled to jump in step with a movement that has flared over their heads. In such cases, they come scurrying through the backstairs of the government and obtain permission to head the general strike, with the obligation to conclude it as soon as possible ...’

Finally, Trotsky quoting Engels, says there is ‘the general strike that leads to insurrection’. But he adds, ‘a strike of this sort can result either in complete victory or complete defeat’. The most important factor in determining this is whether there exists ‘the correct revolutionary leadership, clear understanding of conditions and methods of the general strike and its transitions to open revolutionary struggle’.

If the struggle reaches such a stage it raises the question of power. And unless there is a leadership capable of correctly posing the question of power – of leading an assault by the working class on the institutions of the state – then the general strike backfires and the class suffers decisive defeat.

So the slogan of the general strike fits a certain point in the workers’ struggle. But it is wrong to raise it as a panacea before that point is reached. That merely avoids confronting the real needs of the movement. And once the point is reached where the slogan of the general strike is correct, you have then to be ready to supplement it with other slogans that begin to cope with the question of power – demands about how the strike is organised (strike committees, workers’ councils), with how the strike defends itself (flying pickets, mass pickets, workers’ defence guards) and with how it takes the offensive against the state (organising within the army and the police).

There have always been those inside the working class movement who have treated the slogan of the general strike differently. Thus at the time Rosa Luxemburg wrote her Mass Strike pamphlet, Georges Sorel, a French intellectual who sympathised with the apolitical revolutionary syndicalists, wrote his In Defence of Violence.

In it he argued that the main slogan of revolutionaries at every moment had to be the ‘general strike’, because this was a ‘myth’ which educated workers about their own strength and revolutionary potential. For him, the general strike was the revolution. But it could easily be ruined if it was identified with any political aim – so he actually denounced the concrete general strikes that had occurred, like that of Belgium over the franchise and that of Petersburg in 1905.

Such ideas continued to have a following even after the Russian revolution of 1917 had shown how workers could take power. For instance, one of the characteristics of the ultra-left opposition inside the German Communist Party in 1919 was, according to the party leader of the time, Paul Levi, to see ‘the revolution as a purely economic process’, rejecting ‘political means of struggle as harmful’ and seeing ‘the general strike as the alpha and omega of revolution’.

But what was said by ultra left, semi-anarchist elements from one side, could also be said by left and not so left Social Democrats as well. In 1920, when right wing militarists attempted a coup in Germany, the country’s leading trade union bureaucrat, Legien, was prepared to call a general strike to save the necks of himself and his fellow Social Democrat leaders. But it was a purely ‘peaceful’ general strike which could not achieve its demand for a purging of the armed forces because only in some parts of Germany were revolutionaries able to take the initiative in turning the strike into armed action to disarm that army.

In the 1930s the slogan of the general strike against war was taken up by the Independent Labour Party. It had broken with the Labour Party, but refused to turn seriously to a revolutionary perspective. A revolutionary perspective would have meant seeing any war as raising the opportunity for an intensification of revolutionary action. The ILP leaders, however, were not prepared to abandon their essentially parliamentary perspective and raised the slogan of the general strike as a way of avoiding commitment to such action.

When the slogan fits

Today the slogan of the general strike likewise comes from two apparently opposed directions. On the one hand it is raised by people like Livingstone and Benn who have not broken with the idea that what matters is parliamentary action reinforced by extra-parliamentary activity. On the other it conies from sects who refuse to look the reality of the class struggle in Britain today in the face.Revolutionary socialists should argue that the slogan does not fit at the moment because of the way the Labour Party leadership and the TUC general council have sabotaged the movement in solidarity with the miners. But we also have to go on to say something else: if the slogan did fit (and it will do one day) then it would be necessary to raise alongside it slogans about rank and file control and about confrontation with the state.

We are vehemently opposed to people like Kinnock and Willis who oppose general strikes under all circumstances. But that does not mean we fall into the trap of seeing the slogan as a panacea which fits all situations.

That trap means in present circumstances failing to emphasise the immediate concrete steps that can be taken to build solidarity with the miners and to expose traitors like Kinnock and Willis. And it would mean, if the struggle rose to the level of real general strike action, failing to raise the further slogans that alone could lead to victory.

We have to follow Engels, Rosa Luxemburg and Trotsky in avoiding that trap.

No comments:

Post a Comment